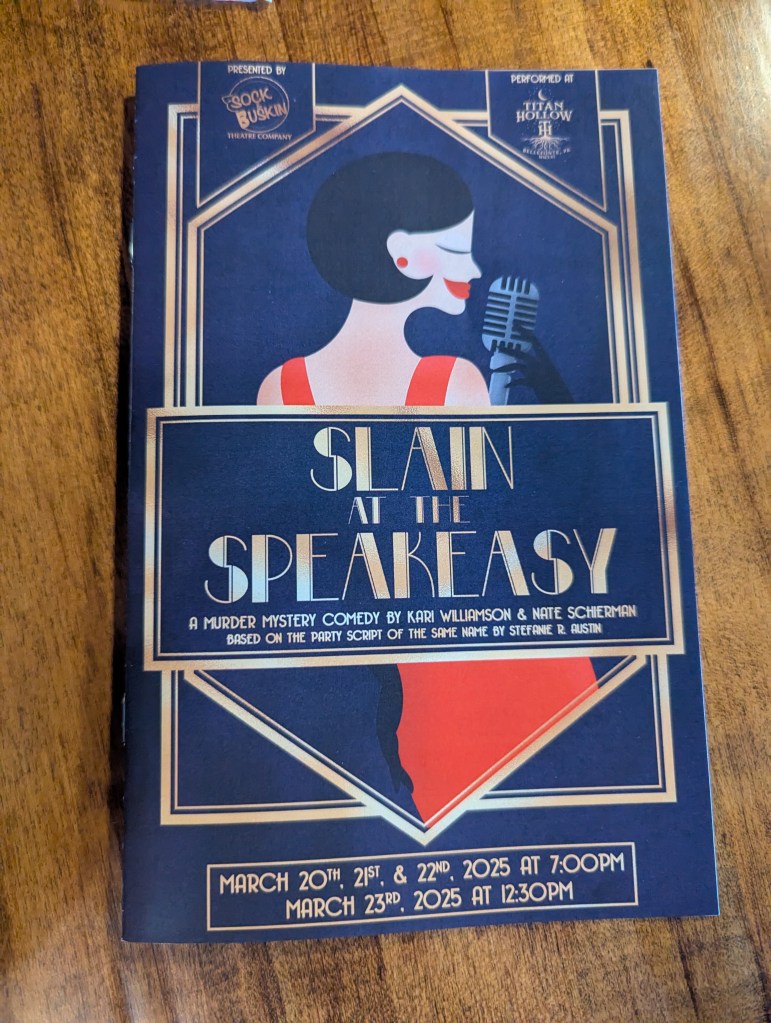

Kari Williamson and Nate Schierman’s Slain at the Speakeasy is a full-length play developed out of an original semi-scripted murder mystery party script by Stefanie Austin, so this is definitely an in-house project for Sock & Buskin Theatre Company. Although this version was based on the original, the full-length production—directed by Henry Morello—doesn’t require audience familiarity with the murder mystery party.

The show is set in Ruth’s, a speakeasy in 1928 frequented by gangsters, jazz singers, and an increasingly drunk chief of police. Ruth Mason owns the place, and maintains two rules: no business and no guns. Her daughter Louise manages the bar, and the main attractions are Annie Marconi’s singing voice and the great alcohol supplied by the mysterious Moonshine Mary, who has been cutting into the business of both Frankie (the local mafia boss) and Nicky (the mafia boss from the next county over). Both Frankie and Nicky have come to Ruth’s to try and find out who Moonshine Mary is, and to try and persuade Louise to buy their booze. Caught between them is Bugsy, who is working for both bosses without the other knowing. Bugsy is also dating Dorothy, Ruth’s cigarette girl, but cheating on her with Rosie, who is Frankie’s girl. Also in the speakeasy are William Werner, the chief of police who is on both Frankie and Ruth’s payroll, and is supposed to be investigating the murder of Ruth’s husband Jimmy—though it’s been weeks and he hasn’t made much progress. And finally, Maxwell Parker, a PI whom Annie has hired to try and solve Jimmy’s murder. As accusations fly about Jimmy’s murder, Bugsy’s cheating, and who the identity of Moonshine Mary, Ruth struggles to enforce her rule against business, because Frankie and Nicky continually try to persuade Louise to buy from them. When Bugsy is found murdered with rat poison, Maxwell—the only one who was onstage at the time and therefore not a suspect—takes over the investigation, asking for help from the audience. The actors circulate among the audience, answering questions and trying to divert suspicion from themselves. Finally, Maxwell—with the help of the rest of the cast—go through all the suspects, eliminating them one by one until the guilty party is revealed. The show is also interspersed with various comic references both contemporary and anachronistic. For instance, early in the show, Annie says, “There’s no better time to invest in the stock market than 1928,” and later on there’s an extended bit where Annie, Micky, and Maxwell make Michael Jackson references, then Frankie (who isn’t the cleverest guy) bursts in with a Prince reference, and they all mock him—to which Frankie says “Relax.”

Sock & Buskin performances are consistently excellent, and this was no exception. Each performer brought their own unique style to the character, creating a distinctive set of personalities that felt unique while also fitting in the broad genre of the noir 1920s detective story. For instance, Jack Donahue (Maxwell) played the noir-style detective, with voice over parts in which he spoke directly to the audience, informing us about how the investigation was going, etc. His overconfidence was well-played, with a series of poses struck for emphasis at various points, often with a sudden turn and double finger guns. This repeated gesture built the persona. Similarly, Andrea Boito’s (Ruth) constant use of the broom to threaten or drive unruly patrons out of the speakeasy became a kind of trademark move, to the point where she threatened to get her broom when answering audience questions. Everyone in the cast gave a top notch performance, bringing a comic version of a 1920s speakeasy to life.