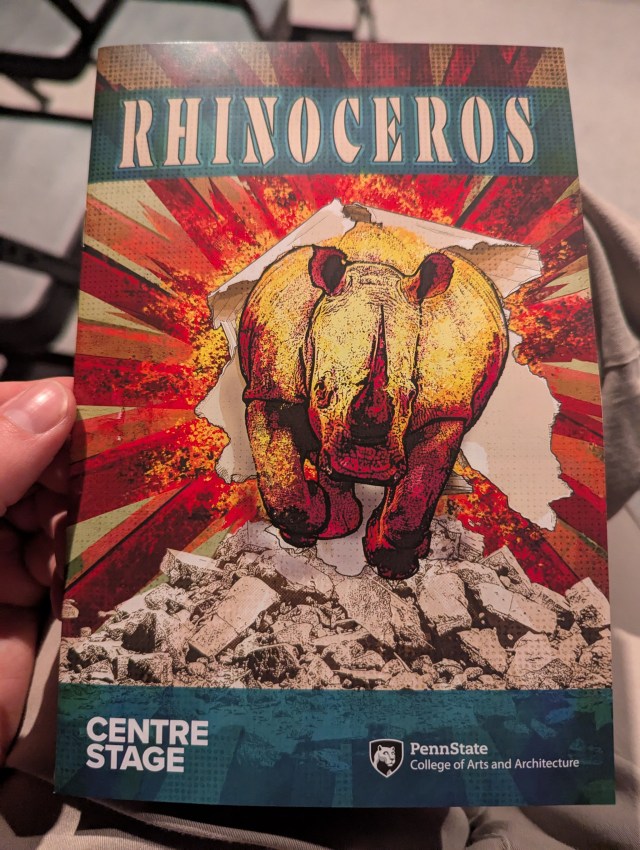

Apart from Shakespeare, one of the first genres of drama I really fell in love with was theatre of the absurd, and so when Penn State’s school of theatre announced that it was opening the 2025-26 season with Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, I was thrilled to see what they’d do with it. Under the direction of Sam Osheroff, the production was very effective.

The play follows a young man named Berenger, who is afflicted with all kinds of anxieties, neuroses, and confidence issues—not to mention being an alcoholic. He’s out at a café with his friend Jean, who is berating Berenger for drinking so much rather than cultivating his mind, when a rhinoceros charges along one of the streets beside the café’s outdoor seating area. Jean and the other denizens of the town are amazed by this—rhinoceroses not being typical fauna for their small French town—while Berenger seems to recognize that the right response is confusion and fascination, but he can’t fully muster those emotions. When a second rhinoceros (or perhaps the same one) runs down the street on the other side of the café, a lively debate ensues about whether it was the same rhino, a different one, and whether one (or both) had only a single horn or whether one (or both) had two horns. Into this argument wades the logician, who uses a spiral of logical propositions and contingencies to not say anything at all—but in a way everyone else finds extraordinarily impressive. Back in Berenger’s office, there’s a lively debate going on about whether the rhinos are real or just a mass delusion. Botard—a conspiracy theorist—asserts that it’s either a mass delusion or some kind of trick by the authorities. On the other side, Daisy actually saw the same rhinoceros (or rhinoceroses) that Berenger did, and she asserts the evidence of her own eyes. She’s joined by Dudard, who is in love with her but didn’t see the rhinoceros (or rhinoceroses) himself. Berenger arrives to confirm the rhinoceros story, then MME. Boeuf arrives to say that her husband cannot come into work today and that she’s been chased to the office by a rhino, who then demolishes the stairs. MME. Boeuf recognizes the rhino as her husband, and she leaps onto his back. From there, people start changing rapidly into rhinoceroses, including Jean, M. Papillion (Berenger’s boss), Botard, the logician, and eventually Dotard. It comes down to only Berenger and Daisy left as humans—possibly in the whole world, but at least in their town. Berenger finally gets the romantic relationship he’d always wanted with Daisy, until she too leaves to become a rhinoceros, fed up with his constant whining, existential terror, and neuroses. Berenger is left alone. Initially he despairs, thinking he may be in the wrong in clinging to his humanity, even trying to become a rhinoceros, but then he regains his senses and ends defiantly refusing to give up his humanity.

The “About the Play” note in the program puts this play in the context of mid-twentieth century European fascism—which Ionesco directly witnessed while living in Romania and France during the 1930s and 40s. I also overheard someone in the audience (whom I believe said they were assistant or associate lighting designer) explaining to some other audience members that Rhinoceros is an allegory for the rise of fascism. These things are certainly true. But this focus on the political dimension also misses a larger philosophical dimension of Ionesco’s play. Absurdist theatre is heavily inflected by absurdist and existentialist philosophy, which is fundamentally concerned with questions about meaning, purpose, and the construction of the self as such. When, for instance, Berenger tells Jean that he drinks because he doesn’t feel comfortable in his own life, doesn’t feel like he fits or has purpose, the character is introducing the existential crisis: the gap between the fundamental meaninglessness of existence and the human desire for a meaning. Often this desire for meaning is filled by conformity to social systems—fascistic sometimes, but also religion, social norms, identifying with a job, revolutionary ideology. Basically, anything external that seemingly gives our lives a sense of purpose. For others, they retreat from the absurdity of a meaningless existence into unthinking contentment—like the bucolic rhinoceroses—rather than accept and confront the absurd. And this is also a crucial philosophical dimension of the play, because Berenger not only stands alone in his resistance to a rising tide of fascism, he also resists transforming into an animal that seemingly does not engage with the larger existential quandaries of life. And while remaining human and confronting his existential angst does not make Berenger happy, he does life truthfully and so in the final moments of the play where he defies the rhinoceroses that make up all of society, he is an existential hero.

The performances for Rhinoceros were extremely good—though I would expect nothing less from Penn State theatre students. Jason Claudio gave a very good Berenger, despite having his arm in a sling (apparently, he dislocated it a couple of times during stage falls in rehearsal). Even with an injury, he foregrounded the constant nervous energy and anxiety of the character by engaging uncertainly with his much more strong-willed friend Jean (Walker Reiss) and being unable to settle into a comfortable cohabitation with Daisy (Teagan Jai Boyd). Reiss was definitely one of the bigger, more comic personalities of the show, from his bold pronouncements in a loud, booming voice, to his colorful clothes that he kept fastidiously tidy (Kathleen Myron was costume designer). Another really funny performance was Logan Uhrich as the logician, who combined an inveterate geekiness with a blustering self-confidence in the unassailability of his own logic. Against these comic roles, Lukyan Silver provided an excellent break in his role as Dudard, performing very seriously and with great restraint. Normally, one looks for a comic relief, but in this case it was a straightman who broke up the general absurdity of most of the performances.

On the technical side of things, the production make some extremely interesting decisions. Probably the biggest technical aspect came during the scene here Jean transforms into a rhino while Berenger is visiting him. The initial phases of the transformation came when Jean removed his pajama shirt to reveal rhinoceros skin across his chest, sides, back, and upper arms—a tight-fitting shirt designed to look like scaly grey-green skin. But things really ramped up when, in the last portion of the scene, five huge pieces of a rhinoceros puppet were brought on stage as the lights dimmed to indicate the existential horror of what Berenger was witnessing. Reiss took the head, and the other puppeteers (the rest of the cast) either controlled the four quarters of the body or moved around the outside of the rhinoceros puppet, periodically mock charging the audience. Visually, it was really cool—the kind of thing one expects to see in big budget theatres. Laurencio Ruiz was puppet designer and mentor.

The other production element I found really fascinating was the hollowness of most of the props. Virtually every prop was an echo of the thing it was supposed to be. The doors to the café or apartments was a door frame with just the external border of a door that swung—but an entirely open middle. Similarly, Berenger’s mirror—with which he obsessively checked for the development of a horn in the last portion of the play—was merely a frame with an open space where the reflective glass would otherwise have been. The cups, flowers, telephone, etc. were all flat, with the design of the thing drawn/painted/printed on the side. So, when, for instance, Berenger poured brandy into a glass and drank it, the bottle and glass were both flat cut outs, roughly ¾” thick, with the image of a brandy bottle or a glass of liquid showing in black and white on both sides. This gave an eerie feeling of the world being two-dimensional, which increased the absurdity of this world.